Behind a nondescript facade in northeastern Milan is the magical residence of Barnaba Fornasetti. It’s a shrine to the style developed by his design-legend father, which still defies categorization.

There is a passageway in the home of Barnaba Fornasetti that is like a portal into the waking-dream universe of his father, the famed designer, artist and engraver Piero Fornasetti. Ascending a flight of stairs — its red-velvet-upholstered railing swaying disconcertingly from side to side with the slightest touch — we turn into a nondescript doorway that deposits us in Barnaba’s LP-lined music room. There’s a sound-mixing board and a CD tower by Atelier Fornasetti resembling a tall building, above which hang old printing tools and shears.

This is Barnaba’s inner sanctum. “At school they said I had my head in the clouds,” he explains. “Sometimes, I took refuge in the world of my imagination. As an adolescent, I developed a passion for music.”

It isn’t until I turn around and look back at the doorway, however, that I realize we’ve actually emerged from an armoire. The home’s eccentric 67-year-old owner has backed one against the entrance and cut an opening the size of the door, so that going into the room requires entering through the back and exiting from the front of this massive piece of furniture. “It was the wardrobe of the carabinieri a cavallo [horse-mounted police force] at the beginning of the twentieth century,” Barnaba explains. “It is so tall because it held their capes.” Popping out of the armoire produces a sensation similar to that often evoked by Piero’s imagery: magical but also a little unsettling.

Barnaba grew up in this house — known as Casa Fornasetti and located in the Città Studi quarter of Milan’s northeastern quarter — which was originally built by his grandfather, an accountant, and has been added onto over generations. The music room is the most recent of Barnaba’s modifications. It’s a statement about his individuality, asserting his personal avocation (music) — although Piero’s presence lingers in spirit and in the form of an Irving Penn–shot portrait, the designer’s unsmiling countenance bluntly confronting the viewer.

“The motifs created by Fornasetti are part of the popular imagery that lies in our collective unconscious,” says Barnaba. “I was born in this context, and my own imagination has been forged by it. I have never tried to differentiate myself. On the contrary, I was assigned the task of carrying forward an important tradition.”

Nevertheless, Barnaba’s adaptations of his father’s designs pack a contemporary punch, which, he points out, is consistent with their eclectic origins. “The sources of inspiration for the Fornasetti visual language are numerous,” he says. “They come from the past, often from classical and neoclassical art, always with respect for the canons of beauty.”

At the height of Piero’s popularity, in the 1950s and ’60s, that language — architectural engravings, suns and moons, houses of cards, animals, mythological figures and surrealistic imagery — adorned furniture, ceramics, scarves and other products, as well as, thanks to frequent collaborations with his mentor Giò Ponti, the interiors of the San Remo Casino and the Andrea Doria ocean liner.

After Piero’s death, in 1988, Barnaba became the keeper of the Fornasetti flame, reproducing his father’s designs and riffing on them in his own furniture and fashion pieces, while also licensing signature motifs for wallpapers, rugs, scented candles and many other items.

These are still sold through the Fornasetti shop that Piero opened on Via Manzoni in the 1950s. “I inherited the store and, over the years, moved it to various locations,” Barnaba says. “Today, it occupies three floors in Corso Venezia, in what was once the site where Filippo Tommaso Marinetti founded the Futurist movement.”

Barnaba’s creations employ more brightly colored and larger-scaled versions of the Fornasetti graphic repertoire. His latest limited-edition series, Architettura Celeste, figuratively blows the roof off and opens the boarded windows of his father’s famous 1950s Architettura design, a grisaille depiction of classical architecture he developed to adorn Ponti’s trumeau, a slender secretary-cum-cabinet that was perhaps the most famous of the furniture pieces he developed with Piero. Barnaba’s take lets light and blue sky into the vaulted spaces, allaying the Giorgio de Chirico–style eeriness and claustrophobia of the original motif.

Barnaba has also become what he refers to as an art director, collaborating on opera sets, museum exhibitions and installations (he’d like to design a hotel as well), often with his companion, Valeria Manzi. One such exhibition, on view now through September 9 at the 15th-century Palazzo Altemps, in Rome, juxtaposes 800 Fornasetti pieces with the palazzo’s classical trappings.

Back in Milan, the U-shaped house embraces a courtyard left wilder than you’d expect in this handsomely tailored city. To the right of the entry hall is the printing room where Piero produced his work, including editions of other artists’ oeuvre (de Chirico, Lucio Fontana and Massimo Campigli, among them ). To the left is Piero’s old studio, graced by a Ponti table decorated with Fornasetti imagery, where he conjured the designs that became ubiquitous in the mid-20th century.

“Despite his limitless creativity,” says Barnaba, “my father was very strict, especially in his work. It was from him that I learned self-sacrifice and attention to detail. From a technical point of view, on the other hand, I received the greatest education from the work of the artisans in the atelier — first and foremost, a man from Puglia who often argued with my father. I became their go-between and that allowed me to learn a lot.”

In fact, Barnaba remembers Piero as an authoritarian and disengaged father for the most part. “He did not give a lot of attention to me, even if I was his only child,” Barnaba says. The child is still in there, behind his bright blue eyes and occasional glimpses of mischief. Like many sibling-less children more used to adult company than that of his peers, he can also be deferential and retiring. “I am quite shy,” he admits. “At the same time, I like having people in the house because it’s quite big.” The guest list for his party (which he deejayed) on the closing night of this year’s Salone del Mobile numbered more than 1,000.

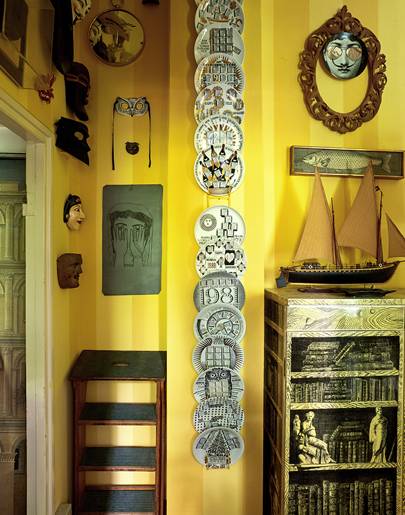

Beyond the studio is a corridor papered with Gerusalemme, a wallcovering replicating a 1949 Fornasetti design, on which hang artist proofs Piero printed for his contemporaries. Continuing on past the stairs, however, you come to a bathroom tiled in a checkerboard pattern in which solid black squares alternate with ones depicting Tema e Variazione, arguably Fornasetti’s most iconic image: the face of 19th-century soprano Lina Cavalieri in hundreds of incarnations — as a clock, a wheel of cheese, an Arab woman and wearing mirrored sunglasses reflecting the Paris skyline. Outside the bath, are selections from a series of 69 erotic drawings Piero completed over several years.

Farther down the hall is the former dining room, now an emerald-green living room appointed with white chesterfields, a Fornasetti Città che si rispecchia cabinet, a 17th-century Dutch mirror over the mantel and bookshelves flanked by a spectacular pair of six-foot-high etchings of Trajan’s and Marcus Aurelius’s columns. Across from these is a window where an array of Biedermeier goblets in many colors catches daylight and refracts it in different shades around the room. The house is a dense omnium-gatherum. Every nook and cranny is occupied by objects both common and rare.

“I am a bit bulimic about collecting,” Barnaba says, explaining the densely possession-packed interiors. “But I try to limit myself, especially in recent years, so as not to be overwhelmed by it.” Yet clearly this rich mash-up is essential to his soul and creativity. “It’s difficult for me to be in a minimalist environment. I can spend a couple of weeks in a simple hotel by the seaside, but normally I suffer a little bit.”

On the second floor is Barnaba’s childhood bedroom, now a guest room decorated with Fornasetti coral-themed wallpaper and a grouping of fish-themed trays. From the daybed, Smoke, a charcoal-gray cat who rules the roost with Fay, a silvery brown-coated feline, wakes briefly to eye us with indifference. Next door is the former master bedroom, which contains the original gilt-iron bed

, end tables sporting putti and a Fornasetti Architettura chest. The walls are now papered in Nuvole, a cloud pattern Barnaba developed with Cole & Son. His mother, Giulia, lived here until she died, in 2009.

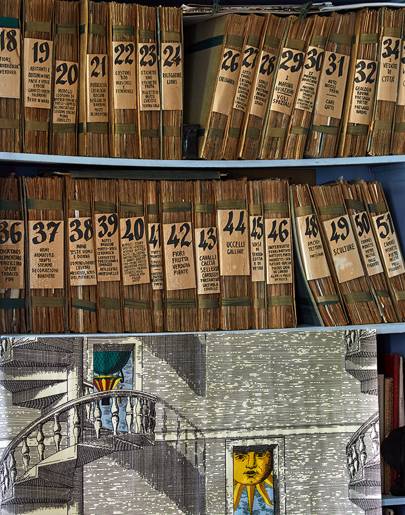

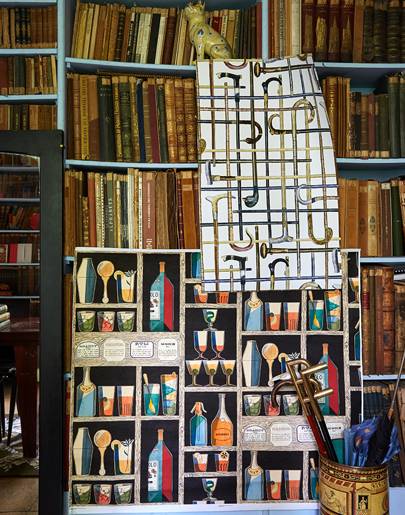

Back down the hallway, through the carabinieri wardrobe and past the music room is the “blue library,” another space lined with shelves, these holding antique books from which Piero ripped pages illustrating things he liked. When the Fornasetti look fell out of fashion and the firm ran into financial troubles, in the 1970s, a book expert was brought in to appraise what appeared to be a substantial holding. But because some of the volumes were missing pages, they proved worthless.

In one corner of the library is a door to the “red room,” re-created from the family’s villa in Como. It’s decorated with red shag carpeting, red walls, a red-shaded lamp, a red Sole cabinet — even the books in the built-in shelves are red or have the color in their titles: Stendhal’s Le Rouge et le Noir, Mao’s The Little Red Book, Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter. The room reflects both Barnaba’s prankish inner youngster and his need for personal space. He has said that no guest can tolerate staying there for more than three days, and that’s the intended effect.

The house itself is a manifesto for Barnaba’s vision of the Fornasetti brand. “My purpose,” he states, “is to make Fornasetti decoration available without necessarily buying an object, to find new ways of using decoration in other fields that are open to a broader audience.”

During last year’s Salone, he gave the historic San Glicerio obelisk near the center of the city a makeover by wrapping it in a pattern of Fornasetti lips. The design, he says, “fills a cherished district with kisses during the Milanese carnival of the Salone del Mobile, that moment when the city stages its finest show, a show in which art and craftsmanship meet industry. Precisely that union so desired by the utopian vision of Ponti and Fornasetti.”

And Barnaba’s home is, in effect, an entire Fornasetti universe, with all the fantasy and dream-world aura that implies.

This article was originally published in Introspective Magazine by 1stbibs

and House and Garden Photos courtesy : Oberto Gili