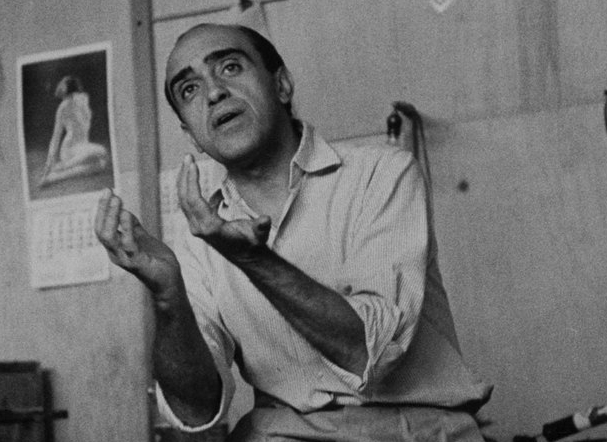

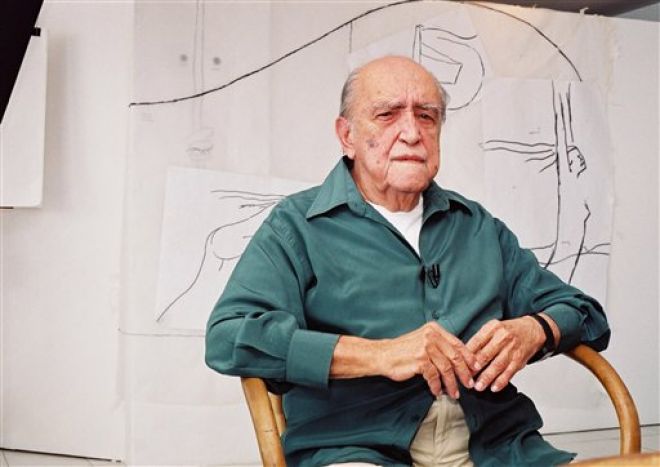

Oscar Niemeyer, the last lion of architectural modernism and the most renowned cultural figure in Brazil, died Wednesday at age 104. Here, in a review essay originally published in The Atlantic magazine in 2008, literary and national editor Benjamin Schwarz appraises Niemeyer’s life and work, focusing on the architect’s most colossal, enduring, and controversial work — the city of Brasilia.

It was a heroic and inhuman scheme. From 1956 to 1960, Brazil — in an effort to cleanse itself of its colonial past, to flee its burgeoning social afflictions, and to fulfill its long-prophesied emergence as a great power–conjured a new capital, Brasília, on an empty plateau in an endless savanna 3,500 feet above sea level. The city’s planner, the architect Lúcio Costa, found the setting “excessively vast … out of scale, like an ocean, with immense clouds moving over it.” No invented city could accommodate itself to this wilderness. Instead, Costa declared, Brasília would create its own landscape: he devised a city on a scale as daunting as the setting itself. In conformity not with its environment but with those modernist utopian theories of the rational, sterile “Radiant City,” Brasília was not to grow organically but to be born, Costa said, “as if she had been fully grown” — he even refused to visit the site, because he didn’t want reality to impinge on the purity of the original design. Brasília was the first place built to be approached by jet, and the city’s roads — inspired by Robert Moses’s deadening expressways belting New York’s outer boroughs — were like runways. Here was a city without a traffic light, containing thoroughfares without crosswalks. The result was (or should have been) obvious, as Simone de Beauvoir reported after visiting Brasília the year it was inaugurated:

What possible interest could there be in wandering about? … The street, that meeting ground of … passers-by, of stores and houses, of vehicles and pedestrians … does not exist in Brasília and never will.

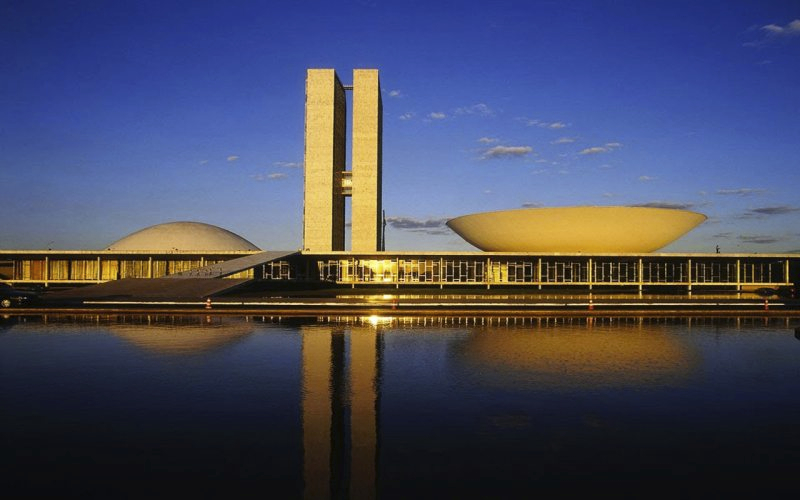

Today, the city is quite correctly regarded as a colossally wrong turn in urban planning–but Brasília, paradoxically, contains some of the most graceful modernist government buildings ever produced. All were designed by Oscar Niemeyer (now 100 years old and still working), who helped select Costa’s master plan and who was the creative influence behind the building and shape of the city. Both facts must be considered in any effort to reckon the legacy of Niemeyer — the last great architect of the modernist ascendancy — and his relationship to modernism, a relationship that both spurred and warped his creative achievement.

A crop of books published over the past few years illuminates both Brazil’s extraordinary achievements in modern architecture from the 1930s to the 1960s (Lauro Cavalcanti’s clear and intelligent When Brazil Was Modern and the ambitious if at times pretentious Brazil’s Modern Architecture, edited by Elisabetta Andreoli and Adrian Forty) and specific aspects of the career of Niemeyer, an architect revered in his country as its greatest living cultural treasure (Oscar Niemeyer: Houses, by Alan Hess, and Modernist Paradise, by Michael Webb, an opulent explication of the only Niemeyer-designed residence built in the United States). These join such older works as Brazil Builds, the Museum of Modern Art’s seminal introduction to Brazilian modernism; Henrique E. Mindlin’s Modern Architecture in Brazil; Norma Evenson’s Two Brazilian Capitals: Architecture and Urbanism in Rio and Brasília; David Underwood’s Oscar Niemeyer and Brazilian Free-Form Modernism; and Niemeyer’s self-indulgent but (intentionally and otherwise) revealing memoir, The Curves of Time.

None of these books approaches Styliane Philippou’s forthcoming Oscar Niemeyer: Curves of Irreverence, one of the richest historical, cultural, and aesthetic assessments of an architect’s work I’ve read. To be sure, Philippou, a British architect and architectural historian, indulges in some academic gobbledygook (that marker of hip academese, “the Other,” makes its appearance far too often), but in authoritatively assessing Niemeyer’s work and its place in architectural and Brazilian cultural history, she has marshaled such diverse subjects as 18th-century colonial Portuguese architecture, bossa nova, the topography and cultural geography of Copacabana Beach, and the design-selection process for the UN headquarters. The book is also a marvel of presentation. Philippou fluidly explicates her narrative and arguments with detailed site diagrams and maps; drawings, plans, and elevations; photographic comparisons of buildings historically linked to Niemeyer’s; and her own lavish, precise photography of Niemeyer’s work, including both general views and details.

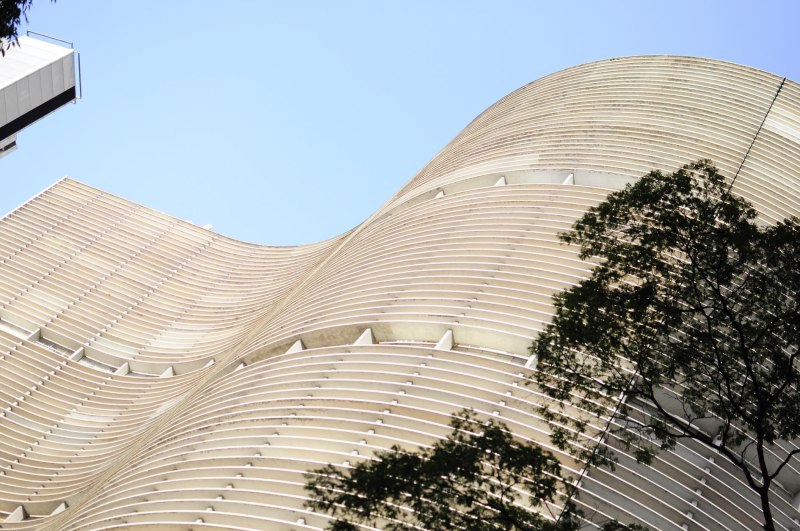

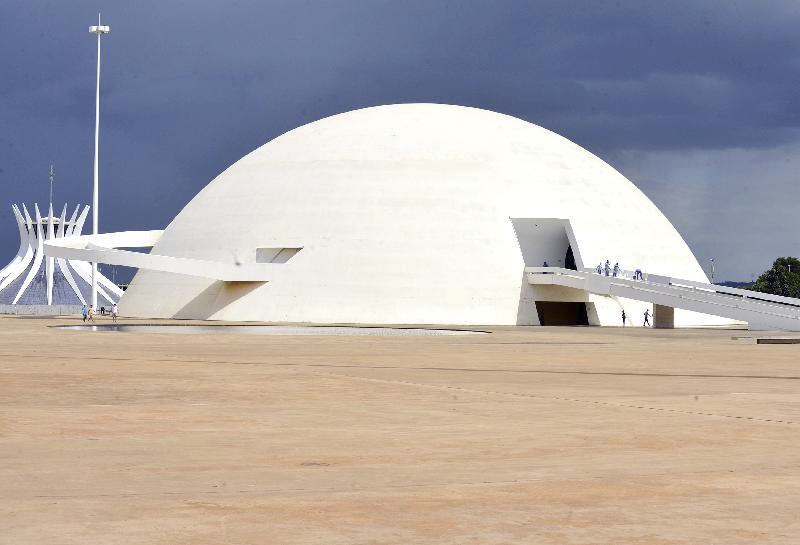

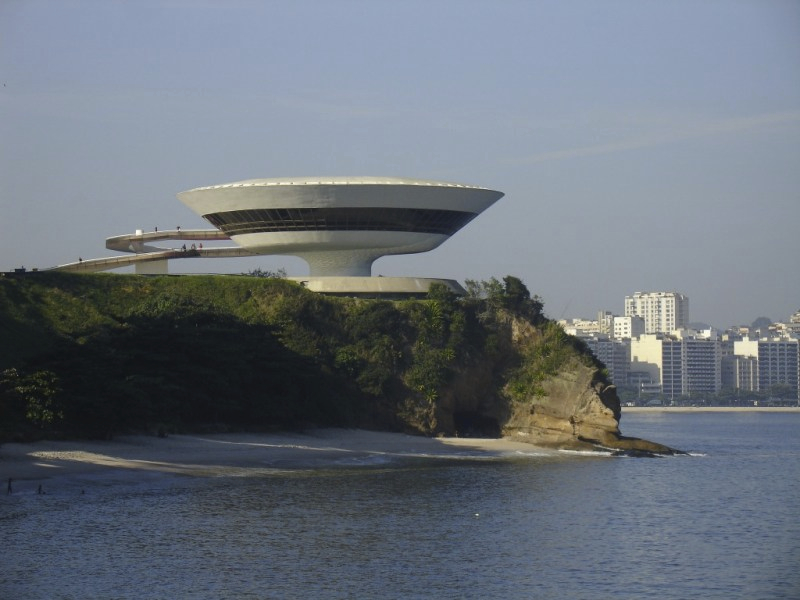

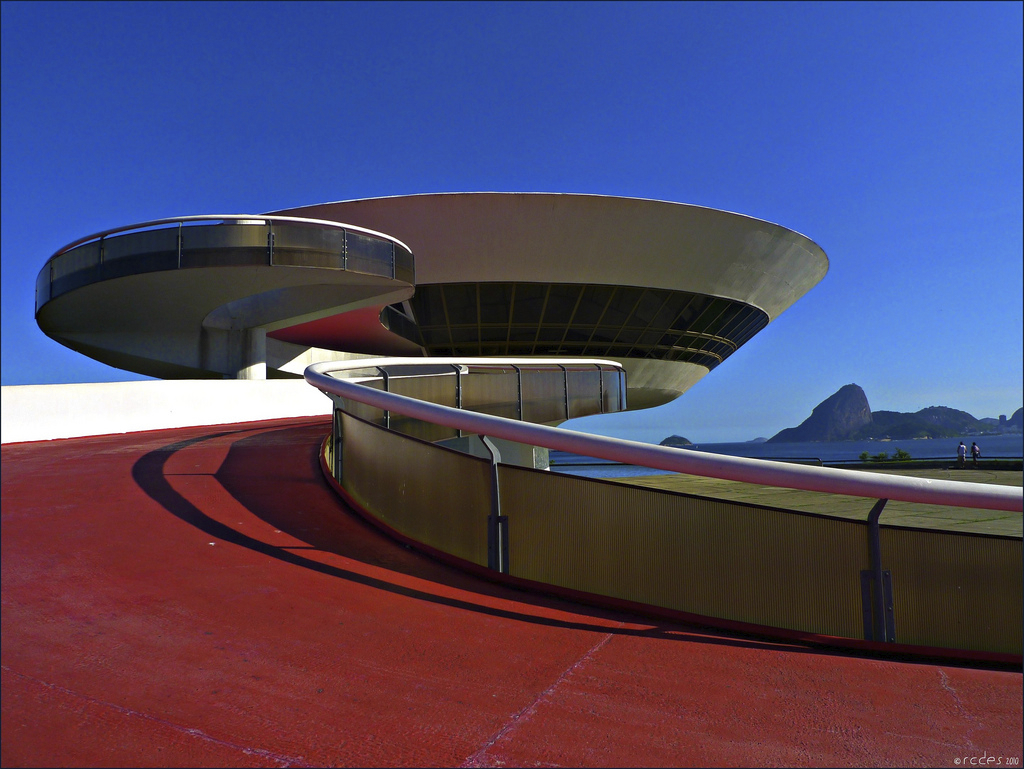

Although he was a disciple of Le Corbusier’s and clearly embraced modernism, Niemeyer, with his love of curves and organic shapes, offered a jaunty alternative to the geometric severity of the International Style (a “monotonous and repetitive architecture … so easy to create that it quickly spread from the United States to Japan,” as he characterizes it in his own, often repetitive, memoir). Confirming Niemeyer’s assertions, Philippou repeatedly shows how eroticism inflected Niemeyer’s approach–“form follows feminine” is one of the architect’s many, somewhat tiresome, pronouncements–and how that approach quite literally grew out of his girl-watching (something of a dirty old man, he’s forever explaining his architecture by sketching women’s breasts and backsides for mock-scandalized journalists). He was obviously also inspired by the undulating beaches and topography of his native Rio de Janeiro (his longtime studio, in the penthouse of an Art Deco landmark building, takes in famously sweeping views of Copacabana and Sugarloaf).Philippou demonstrates that Niemeyer’s highest achievements are profoundly informed by a Brazilian aesthetic, which has long made sinuous forms a basic element of its vocabulary (see the mosaic pavements of alternating black and white waves, both from the colonial period and, on Copacabana, from the early 20th century). True, since the 1960s Niemeyer’s penchant for curves and, worse, flying-saucer shapes has gotten the better of him (a penchant he could indulge because of engineering advances in his favorite medium, reinforced concrete, that increased the plasticity of that already famously plastic material) — too many of his later buildings, such as the 1996 Museum of Contemporary Art in Niterói, smack of kitschy Futurama.

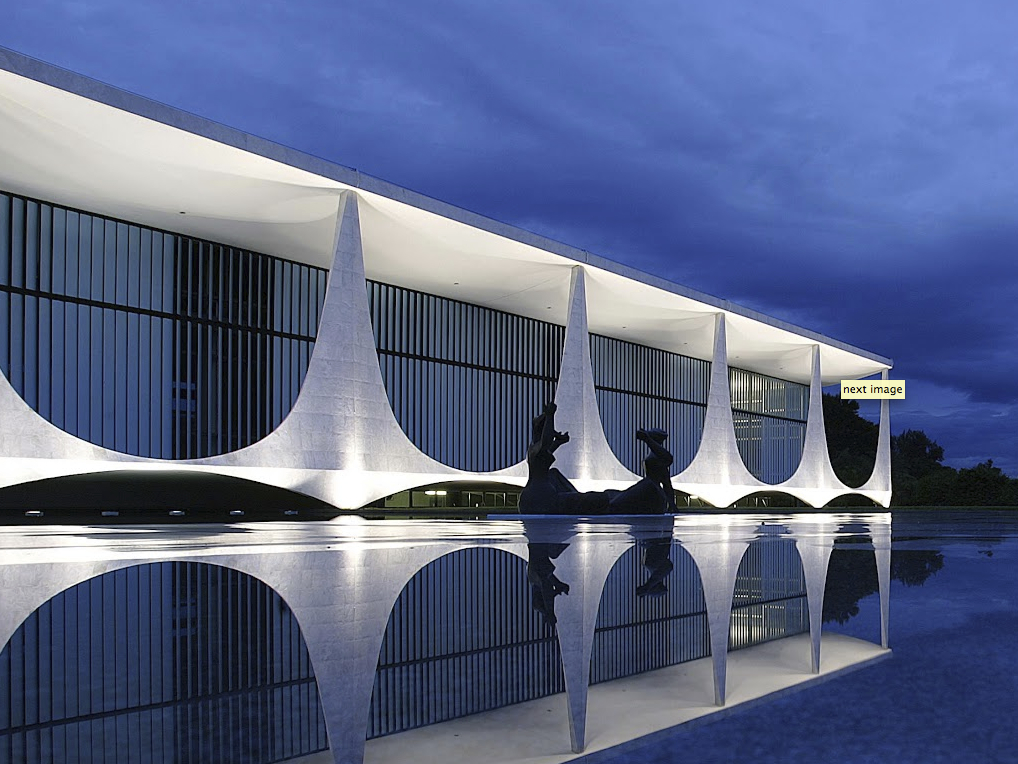

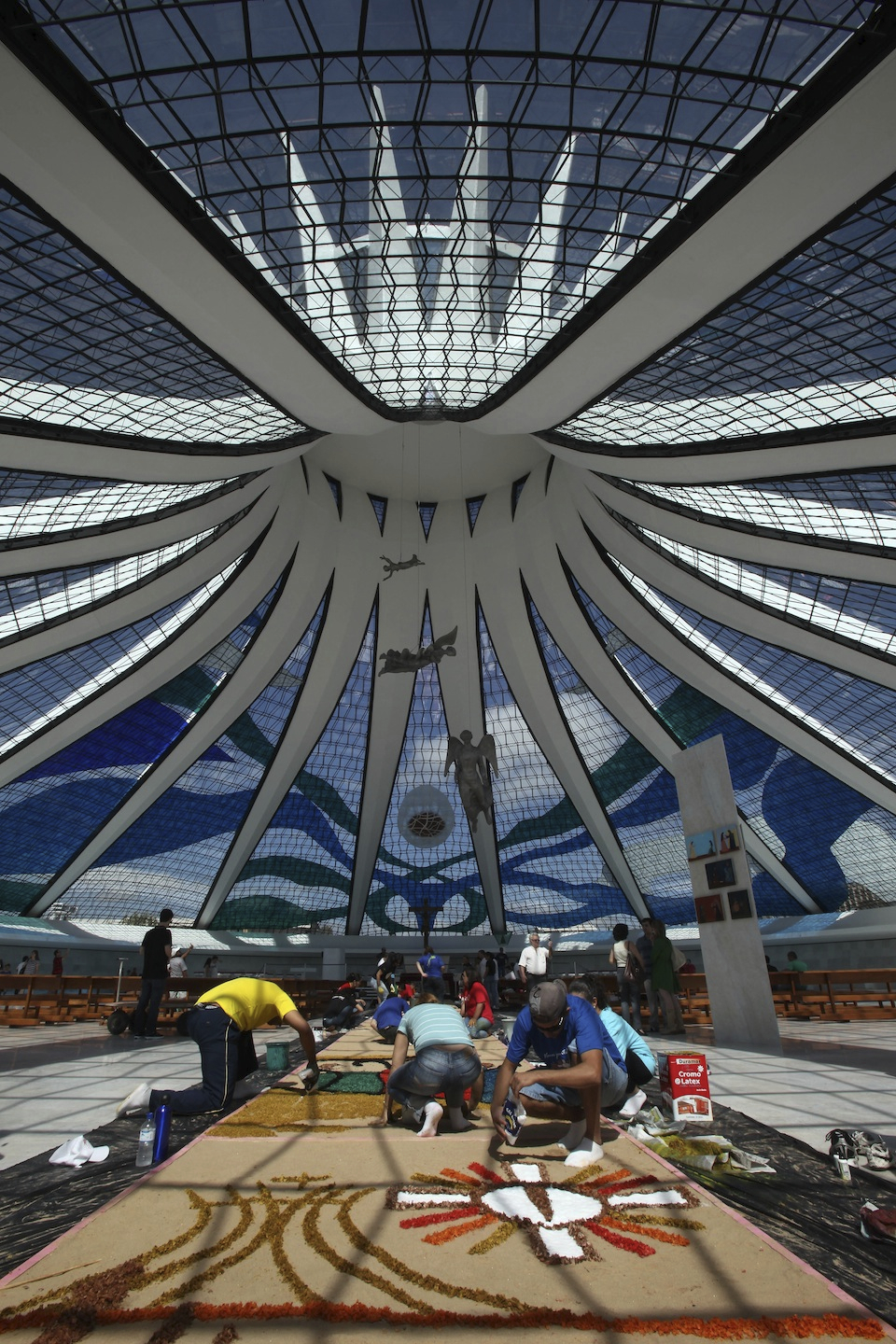

All of Niemeyer’s early masterpieces–the Brazilian Pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair and the Casino in Pampulha, buildings that married the precision and clarity of the International Style with sinuous, organic lines; the Boavista Bank building in Rio, whose undulating glass-brick walls covering its rear and lateral facades created “one of the most beautiful internal spaces of modern architecture,” as Cavalcanti correctly avers; his house at Canoas, which roofed a slick glass pavilion with a seemingly weightless, free-form concrete slab resembling a lily pad, thus creating a shady overhang that allowed the outdoors and indoors to merge–fused modernism’s astringent grace with a sauntering, often lyrical style. That approach would culminate in Niemeyer’s three best “palaces” in Brasília: the presidential residence, the Foreign Ministry, and the Supreme Court. These seats of power were in fact inspired by houses (fazendas, those colonial Brazilian, low-slung plantation houses with their colonnaded verandas), which helps account for their unintimidating grandeur. With their poised and delicate colonnades and their almost buoyant, paper-thin platforms and roofs, these limpid buildings fairly float upon their sites. They’re at once monumental and ethereal, as Philippou makes clear:

The Supreme Court’s columns em-brace the glass box … like pleats fluidly unfolding and refolding, carrying the eye along. Their marble cladding touches the earth at one infinitely small point … The fluid, fan-like effect is best appreciated when walking along the verandas: the great white marble leaves open and close languorously, in slow, perpetual motion, seemingly the source of the cool breeze under the large roof overhangs.